Vigils have been held to commemorate the disaster, where an explosion and fire released a large cloud of radioactive contamination into the air, spreading over much of Western Russia and Europe.

No doubt the anniversary has extra resonance following recent events in Japan, at the Fukushima nuclear plant.

However, the relevance of today’s date for Naked Security is the virus that bear’s Chernobyl’s name.

The CIH virus, also known as Chernobyl, was first discovered in 1998, and quickly became one of the most commonly encountered viruses in the wild.

Although never as widespread as other malware of the time such as the Melissa virus, the CIH virus still appeared high in the malware charts. The fact that a number of magazine cover CDs appeared, with programs infected with CIH, no doubt assisted its wide distribution.

But it was CIH’s payload which created the biggest cause for concern.

CIH was dubbed “Chernobyl” by the media because it was programmed to activate its destructive payload on the anniversary of the Chernobyl reactor meltdown – 26th April – wiping data from victims’ hard drives and overwriting the computer’s BIOS chip, making the computer unusable.

And don’t forget – on some computers, the BIOS chip wasn’t removable, and so it could only be replaced by swapping the entire motherboard.

For such a destructive computer virus to be so prevalent, and with April 26th 1999 approaching, was a real cause for concern. And in Asia it was reported to hit particularly hard.

For instance, South Korean government reports claimed that the Chernobyl virus caused $250 million damage, infecting a quarter of a million computers.

So who wrote the Chernobyl virus, and why?

The first point to bear in mind is that there’s no suggestion that the author of the virus intended it to be called “Chernobyl”. That was a name dreamt up purely because of the coincidence of the virus’s payload activation date, rather like the infamous Michelangelo virus was so named because it happened to be coded to trigger on the anniversary of the artist’s birth.

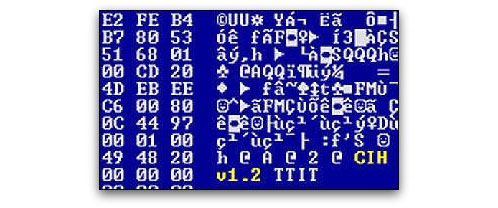

In fact, many in the anti-virus community chose to call the virus by another name – CIH. This name was chosen from a plaintext string inside the virus’s code:

CIH v1.2 TTIT

The Chernobyl name stuck, of course, and helped to fuel headlines about the virus and its particularly devastating payload. Little did we know that the phrase “CIH v1.2 TTIT” would not only help identify the virus’s author, but also where it had been created.

Former classmates at Taipei’s Tatung Institute of Technology said that Chen had boasted of creating the virus, and warned them not to allow their computers to become infected.

I’ll spell it out, in case you haven’t twigged yet:

Chen Ing Hau = CIH

Taipei Tatung Institute of Technology = TTIT

The Taiwanese authorities, it seemed, had got their man and it looked likely that Chen Ing Hau would be punished.

But the story doesn’t end there. Because – astonishingly – although the virus had caused serious levels of damage to computers in many countries no-one appeared to have filed a complaint in Taiwan. And without any local victims coming forward, Chen Ing Hau seemed to have got away with it.

Chen subsequently won a job at a software company on the back of his infamy.

It wasn’t until almost 18 months later, in September 2000, that a Taiwanese student reported his computer had been hit by the virus and Chen Ing Hau was finally detained.

However, as far as I have been able to determine (and I would love to hear if anyone has further information), Chen escaped with a reprimand and was never fined or imprisoned for the CIH virus he created. Possibly the computer crime laws in Taiwan had found to be lacking, and insufficient to form a case against him.

Here’s a photograph of Chen speaking at that conference, in front of a large screen of code discussing how Linux drivers can be reverse engineered.

I wonder if he still signs his code “CIH”?

Viruses like CIH/Chernobyl were becoming a rarity even in the late 1990s. More and more malware authors were turning their backs on destructive payloads, and implementing sneakier forms of attack instead.

As making money, rather than wanton destruction, became the primary motivation for malware authors so cybercriminals realised that attacks which drew attention to themselves with dramatic payloads would work against their plans of stealing information from compromised PCs.